Jewish history is complicated and full of opportunists, sell-outs, optimists, altruists, realists, and dreamers. Depressing reversals of fortune and betrayals are fundamental to any part of it. It's hard to grasp any big picture of Jewish history or identity. So much is distorted, intentionally or through accidents to the people who might have told their story.

Jewish history is complicated and full of opportunists, sell-outs, optimists, altruists, realists, and dreamers. Depressing reversals of fortune and betrayals are fundamental to any part of it. It's hard to grasp any big picture of Jewish history or identity. So much is distorted, intentionally or through accidents to the people who might have told their story.

Can we really picture this all happening against a background of midnight sun (like in this photo I stole from some chamber of commerce website, unlike my own original photos of Jerusalem!) Can we see these yids, as they consistently call themselves, in an imaginary Alaska November with snow, sleet, rain and cold? Well, we have to.

Can we really picture this all happening against a background of midnight sun (like in this photo I stole from some chamber of commerce website, unlike my own original photos of Jerusalem!) Can we see these yids, as they consistently call themselves, in an imaginary Alaska November with snow, sleet, rain and cold? Well, we have to.

"WE'RE going through!" The Commander's voice was like thin ice breaking. He wore his full-dress uniform, with the heavily braided white cap pulled down rakishly over one cold gray eye. "We can't make it, sir. It's spoiling for a hurricane, if you ask me." "I'm not asking you, Lieutenant Berg," said the Commander. "Throw on the power lights! Rev her up to 8500! We're going through!" The pounding of the cylinders increased: ta-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa. . . .

"Not so fast! You're driving too fast!" said Mrs. Mitty. "What are you driving so fast for?"

So begins "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty." For him, all engines went ta-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa especially when he heard his own old car making the noise, a background to whatever adventure he was having.

As we drove along in an ancient and venerable Ford today, Olga suddenly understood what sound Walter Mitty was hearing: poketa poketa... went our vehicle's distributor, sparking its sparkplugs and just its general reluctance to go slow enough for the safetey concerns of the village, using its two forward gears. Does it use unleaded gas? Well, yes, it was built before gas was leaded (and later unleaded).

After our ride in the old ford, we enjoyed a number of different sights in the village.

Here is how the audience filed through the woods. In the foreground is my friend Olga, who's visiting us this week:

Here is how the audience filed through the woods. In the foreground is my friend Olga, who's visiting us this week: The players bowed as the audience applauded and the sun was setting behind the trees. The only odd sensory experience was a miasma of insect repellent that people sprayed on themselves throughout the play.

The players bowed as the audience applauded and the sun was setting behind the trees. The only odd sensory experience was a miasma of insect repellent that people sprayed on themselves throughout the play.

Bevington's Wide and Universal Theater demonstrates that every age had a new way to visualize and present Shakespeare, and that the 19th century was especially prone to make every word into a concrete onstage image, while 20th century performances sometimes are more abstract than the original productions at Shakespeare's Globe. Here's an image I found that really goes over the top, painted by Alma-Tadena in 1883.

Bevington's Wide and Universal Theater demonstrates that every age had a new way to visualize and present Shakespeare, and that the 19th century was especially prone to make every word into a concrete onstage image, while 20th century performances sometimes are more abstract than the original productions at Shakespeare's Globe. Here's an image I found that really goes over the top, painted by Alma-Tadena in 1883.

The Shadow Catcher is a highly enjoyable novel. The frame story uses a device that seems to be coming up in a lot of very recent books: the main character, who tells the story, has the same name as the author, and seems to have many similar characteristics. "Marianne Wiggins" -- the character who might be the author -- begins with some observations about artwork: "Let me tell you about the sketch by Leonardo I saw one afernoon in the Queen's Gallery in London a decade ago, and why I think it haunts me." (p. 1)

The Shadow Catcher is a highly enjoyable novel. The frame story uses a device that seems to be coming up in a lot of very recent books: the main character, who tells the story, has the same name as the author, and seems to have many similar characteristics. "Marianne Wiggins" -- the character who might be the author -- begins with some observations about artwork: "Let me tell you about the sketch by Leonardo I saw one afernoon in the Queen's Gallery in London a decade ago, and why I think it haunts me." (p. 1)

Around a month ago, I read reviews of several new books on Shakespeare, and decided to read David Bevington's new book This Wide and Universal Theater. I've now obtained it, and I'm in the middle -- and finding it better than I even expected.

Around a month ago, I read reviews of several new books on Shakespeare, and decided to read David Bevington's new book This Wide and Universal Theater. I've now obtained it, and I'm in the middle -- and finding it better than I even expected.

Miriam got a huge pile of presents for her birthday on Saturday. She really likes them, and is sharing them with Alice. One great gift was a snap-circuits toy from Aunt Elaine. As soon as she saw it, Miriam -- who had played with snap-circuits at school -- said she wanted to make a flying saucer. This involves wiring up a twirling device that launches a wheel into the air. The 2-story front hall is a perfect location for launching this. She has also made a sound detector and an OR-logic gate with a lightbulb, following the directions with a little help and explanation. We also played one game of Mousetrap: a very nice gift.

Miriam got a huge pile of presents for her birthday on Saturday. She really likes them, and is sharing them with Alice. One great gift was a snap-circuits toy from Aunt Elaine. As soon as she saw it, Miriam -- who had played with snap-circuits at school -- said she wanted to make a flying saucer. This involves wiring up a twirling device that launches a wheel into the air. The 2-story front hall is a perfect location for launching this. She has also made a sound detector and an OR-logic gate with a lightbulb, following the directions with a little help and explanation. We also played one game of Mousetrap: a very nice gift.

Last night and this morning, Miriam and Alice were playing with two Bratz dolls: Yasmin, a gymnast, and Chloe, a soccer player. As documented in Consumer Reports, removing the dolls from the fetters and shackles of cardboard, plastic, nylon rope, and metal twisters was challenging and time-consuming, but I succeeded without snipping off any hair, clothing, or limbs.

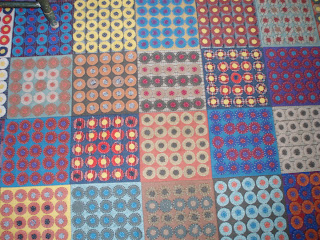

Last night and this morning, Miriam and Alice were playing with two Bratz dolls: Yasmin, a gymnast, and Chloe, a soccer player. As documented in Consumer Reports, removing the dolls from the fetters and shackles of cardboard, plastic, nylon rope, and metal twisters was challenging and time-consuming, but I succeeded without snipping off any hair, clothing, or limbs. Here is a repeat of a photo from my last morning in Istanbul: the Grand Bazaar. We enjoyed the vastness of it all, the painted archways, narrow streets, and constant invitations to look at rugs, scarves, jewelry, tiles, purses, shoes, leather jackets, trinkets, inlaid boxes, more rugs, and so on, I wrote.

Here is a repeat of a photo from my last morning in Istanbul: the Grand Bazaar. We enjoyed the vastness of it all, the painted archways, narrow streets, and constant invitations to look at rugs, scarves, jewelry, tiles, purses, shoes, leather jackets, trinkets, inlaid boxes, more rugs, and so on, I wrote.

Here are some of the guests at Linda and George's Mother's Day brunch. For the food, see the food blog --

Here are some of the guests at Linda and George's Mother's Day brunch. For the food, see the food blog --In his new book, The Islamist, Husain identifies a professed horror of western decadence as the next, infinitely promising excuse for Islamist murder. "When the political pretexts of Palestine and Iraq have been dealt with," he writes, "Wahhabi-inspired militants will turn to other social grievances. Drinking alcohol, 'impropriety', gambling, cohabitation, inappropriate dress - these and a host of miscellaneous others will become excuses for jihad, for martyrdom, feeding the tumour of Islamist domination which grows in the Wahhabi and Islamist mind."I especially like this quote:

...Following a period in modestly dressed, porn-loving Saudi Arabia, Husain concluded that the Islamists' depiction of the west as morally inferior was nothing more than "Islamist propaganda, designed to undermine the west and inject false confidence in Muslim minds". And whether through accident or design, the propaganda is working brilliantly, as it coincides with an epidemic of binge drinking, super casinos and intermittent moral panic.

Writers whose suspicions would be instantly aroused by, say, a smarmy TV evangelist who seemed obsessively interested in fornication, or a politician who relied on divine inspiration as a justification for war, seem to have no difficulty listening to the strictures of angry young men whose primary moral interest appears to be in telling women what to wear on their heads.This is a really good article in the Guardian online -- see: Catherine Bennett: Why should we justify ourselves to those who would bomb us?

Mine was a kind father but a melancholy man. All day long he worked at the factory, measuring lengths of timber with his thick fingers. He fed the timber to the jigsaw with his workman's hands. Sometimes in the evenings he would tell me stories, for in late middle-age he had remembered the stories of his youth: about Sandalfon, the guardian angel of birds, who was responsible for forming children in the womb, and about Metatron, author of the Book of Secrets and God's heavenly scribe. About Moses, who saw God through a clear glas and Elijah, who saw him through a darkened one. About the dangers of moonlight and about the resurrection of the dead. At weekends we walked the streets of our neighbourhood, stole raspberries from Mr. Mankin's garden, bamboo sticks from the municipal park. We picked up coins from the pavement and jewellry from gutters, and wherever we went I ws taught the pleasures of being light-fingered and sharp-eyed.Another passage, about her return to Jerusalem, that I liked:

There was also education by omission. My mother took responsibility for that. (p. 146)

I came to Jerusalem at night, in darkness, after a long absence, rain streaking the windows of the taxi as we rode from the plain to the hills. Outside, at first, there were bright signs, a golden egg, a drive-thru takeaway, a gian smile surrounded by flashing lights. We might have been in America. We might have been anywhere. Then we were on the highway. We were nowhere. Darkness, hunched trees. A change in the air. A whiff of petrol and bitumen, a hint of the sea or the desert. Strangeness. Rain.

Then as we began to climb I closed my eyes and thought I had recognized the old route, its rises and turns inscribed on my memory. But the road had changed. It had flattened, uncoiled and stretched itself into something unfamiliar. And when I opened my eyes, instead of the darkness of the hills there were masses of lights, strings and clusters of lights as far as the eye could see.

"What's that?" I asked.

The driver answered: "That's Jerusalem." (p. 11)