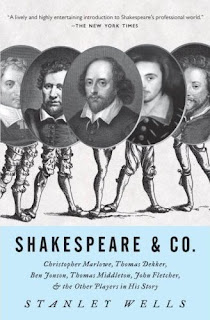

I read Shakespeare & Co. by Stanley Wells because of Bill Bryson, whose Shakespeare: The World as Stage so often quoted the author. While I was disappointed in Shakespeare & Co. as a whole, I found that it triggered my imagination. As I read, I was frequently visualizing what it must have been like in Shakespeare's day to attend theater performances, and what the playwrights had to deal with, besides rivalries, getting paid, and keeping ahead of the censors. Although Wells doesn't write vividly, he logs a lot of source material. Here are some of the things I learned or thought about.

I read Shakespeare & Co. by Stanley Wells because of Bill Bryson, whose Shakespeare: The World as Stage so often quoted the author. While I was disappointed in Shakespeare & Co. as a whole, I found that it triggered my imagination. As I read, I was frequently visualizing what it must have been like in Shakespeare's day to attend theater performances, and what the playwrights had to deal with, besides rivalries, getting paid, and keeping ahead of the censors. Although Wells doesn't write vividly, he logs a lot of source material. Here are some of the things I learned or thought about.A theater in Shakespeare's time could be open-roofed, like Shakespeare's Globe, and lit by daylight. Other theaters were enclosed and lit by candles. The candle-lit theaters may have forced the division of plays into acts and scenes, for a pause to relight the candles. In open-air theaters, action could be nonstop.

Audiences -- who came from all social levels below the monarch -- ate, drank, and moved around during the performance more than they would now. As for Queen Elizabeth and her successor King James, they had private theatricals that enabled them to enjoy the same plays without mixing with the over-excited spectators at the public theaters.

I found Wells' discussion of child actors interesting. Everyone knows that very talented boys played every woman's role in Shakespeare's plays. What's also interesting is that some of the other companies had exclusively boy actors, who put on complex and demanding plays. Wells suggests that they did a great job of playing all parts, old and young, men and women, and could identify well with their roles.

"Their performances may have had the appeal of miniaturization, an effect not unlike that produced by seeing a Mozart opera performed by puppets. There must surely have been an element of burlesque in their need to wear false beards and artificial bosoms, to pad themselves into portliness, to deepen their voices into martial gruffness or raise them into the squeakiness of senility, and to assume other physical characteristics of adulthood. And there may even have been a touch of ambivalent sexuality in audiences' reactions to the adolescent, or pre-adolescent boys' impersonation of nubile young women and of sexually mature, sometimes corrupt adults." (p. 171)

Wells made some interesting points about the props and costumes used in Shakespeare's day, and included as reference material the only surviving lists of props and costumes. He especially emphasized details of stage business, use of trap doors, and the like. Will Kemp, the comic actor, would dance famous jigs on stage after the performance -- and once as a publicity stunt, jigged for a "9-days wonder" through 100 miles of English countryside. Actors often sang songs as part of the play (famous in Shakespeare, of course). Plays then used so many tricks. Witches and gods appear on stage in Pericles and Cymbeline. A dinner appears and disappears in The Tempest. Dreams, ghosts and visions appear, requiring all kinds of special effects, which had to work in front of a live and very close audience, who sometimes could even purchase seats onstage. (See p. 218 for this discussion.)

Theater goers at the time became familiar with plays and characters. The audience had common stories in mind already, often based on the standard grammar school curriculum of that era. They also liked occasional re-runs, often with new scenes or new twists -- we all learned how Shakespeare adapted plays that had already made a story popular, improving them of course. Wells makes no comparison, but I was often thinking about the TV and movie characters that everyone knows and refers to today. Within one Shakespeare-era play, characters might refer to lines or characters in an earlier popular drama, and the audience would be expected to get the reference.

The amount of regulation and censorship of that time is another interesting topic Wells covers. The "Master of the Revels" had duties to keep theaters in line with regulations and to license each play before it could be performed. Strong oaths were outlawed at one time, and existing playbooks, or scripts, had to be revised to comply. Many political and religious topics were totally illegal. During outbreaks of plague, contagion forced closure of all theaters.

As I say, the level of details about performance was amusing, but I found the book often weakly organized. The juicy bits in the book occur at random in his muddle of chapters. Although each chapter claims to be about a single playwright, the author doesn't stick to any topic particularly, but ranges among many subjects. I found it especially distracting that he discussed the presentation of plays not only in their own time, but also throughout the 400 subsequent years, so suddenly instead of learning about Elizabethan and Jacobean theater style, you are hearing about David Garrick in the 19th century, or a 21st century performance at Stratford, England.

So all in all, if I had to suggest that you read a book on Shakespeare, this would be near the bottom of my list. At the top: James Shapiro’s Shakespeare and the Jews and especially his A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599. I also liked Bryson's book and Will in the World: How Shakespeare became Shakespeare by Stephen Greenblatt.

No comments:

Post a Comment