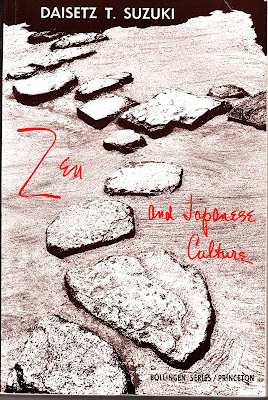

I read Daisetz Suzuki's Zen and Japanese Culture in 1985. I was trying to understand what I had seen at the Ryoanji Zen garden in Kyoto. At the time, I believe I found it quite impenetrable. It's still challenging, but I think I've made progress. For several years after that, I read books on Japan, both fiction and nonfiction, and I think I absorbed quite a lot which stays with me now. I am thinking of revisiting this project, so I reread this book.

I read Daisetz Suzuki's Zen and Japanese Culture in 1985. I was trying to understand what I had seen at the Ryoanji Zen garden in Kyoto. At the time, I believe I found it quite impenetrable. It's still challenging, but I think I've made progress. For several years after that, I read books on Japan, both fiction and nonfiction, and I think I absorbed quite a lot which stays with me now. I am thinking of revisiting this project, so I reread this book.Considering that Suzuki wrote the book in the 1930s, during the rise of Japanese ultra-nationalism, and revised it in 1957, during the end of the Americanization and democratization of Japan, the book is interesting for a lot of things it doesn't say about Japanese warrior culture. He does have a great deal about Zen and swordsmanship. Consider:

What makes Swordsmanship come closer to Zen than any other art that has developed in Japan is that it involves the problem of death in the most immediately threatening manner. If the man makes one false movement he is doomed forever, and he has no time for conceptualization or calculated acts. Everything he does must come right out of his inner mechanism, which is not under the control of consciousness. [p. 182]Suzuki here does not explicitly treat Zen gardens as part of the Zen culture. I think this is because he has quite a long discussion of Zen love of nature. The differentiation that westerners make between nature and gardens doesn't seem to exist in Zen. Who made the natural setting? is not a question for the Zen or Japanese mind. Maybe.

Here are quotes from the book:

What differentiates Zen from the arts is this: While the artists have to resort to the canvas and brush or mechanical instruments or some other mediums to express themselves, Zen has no need of things external, except "the body" in which the Zen-man is so to speak embodied. ... The Zen-man transforms his own life into a work of creation, which exists, as Christians might say, in the mind of God. [page 17]There's much more in this book, and in the many others of this author. A fascination with Buddhism has from time to time been fashionable in American and western thought. Suzuki discussed this trend as it applied to Thoreau and Emerson in the 19th century, and participated in the interest of westerners in the first 2/3 of the 20th century. I wonder if it will come around again soon.

...the experience of mere oneness is not enough for the real appreciation of Nature. This no doubt gives a philosophical foundation to the sentimentalism of the Nature-loving Japanese, who are thus helped to enter deeply into the secrets of their own aesthetic consciousness. [p. 354]