- “Charade” (1963) Chase scene in the Palais Royal with Audrey

Hepburn.

The Palais Royal July 1, 2013:the Buren column installationis very different from what was in the movie.That's me, not Audrey Hepurn, by the way.

The Palais Royal July 1, 2013:the Buren column installationis very different from what was in the movie.That's me, not Audrey Hepurn, by the way. - “Hugo” (2011) Living inside the old Gare de Montparnasse and

the 1930s neighborhood.

Film publicity shot - The Hunchback of Notre Dame (many films) Featuring the cathedral

in one form or another.

Disney - “Last Tango in Paris” (1972) An apartment near the metro

station Passy, as well as many other Paris scenes. I think of the two apartments with towers flanking the station whenever I ride past:

Wikimedia commons - “Midnight in Paris” (2011) Scenes from the life of Gertrude Stein and her cohort from the fantasy of Woody Allen.

- “Night on Earth” (1991) Scenes from infrequently featured

areas of Paris.

- "Ratattouille" (2007) A rat’s point of view of Paris.

Film publicity shot - "Sous les toits de Paris" (1930) I want to see it!

- "Zazie in the Metro" (1960) She never got to ride the metro.

“Louis Malle shows us the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Franz Liszt Square (10th arrondissement), the train station of ‘gare de l’Est,’ a bistro, the flea market of Saint-Ouen, the romantic bridge of Bir-Hakeim, the Galerie Vivienne, the passage Choiseul (2nd district), the banks of the Seine, a cabaret in Pigalle and of course the Eiffel Tower.” (See this post.)

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Paris in Film

Hundreds of films feature action that takes place in Paris. I think you could do an entire tour of the city. I find that the following stick in my mind the most:

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Project Complete

Friday, July 26, 2013

Sunday, July 21, 2013

Wine and War

Wine and War: The French, the Nazis, & the Battle for France's Greatest Treasure by Don and Petie Kladstrup offers a very readable history of France in World War II and immediately thereafter. The book is very focused: it sees events through the eyes of wine growers, wine merchants, and other French men and women in the wine trade, beginning in about 1939 and proceeding historically as the Nazis conquered France. Among many demands, the conquerors required the wine growers to provide them with the best of the wine on hand and the best that could be produced in wartime conditions.

First-hand accounts from letters and diaries, occasional newspaper articles, and interviews with survivors provide vivid evidence for the way that French people experienced the conquest and looting of their country and how they struggled against the occupying forces. Deportations, confiscations of property like vineyards from Jews and others, and the appropriation of food and almost all other necessities to be sent back to Germany come to life in the authors' narrative. The memories of those who spent the war in POW or other camps were especially vivid.

As I read each chapter, I realized that the focus on wine was an effective starting point for the discussion of almost every issue of the war. I was especially interested in the slow and penetrating changes in the way that the French viewed Marshal Pétain and the Vichy government. At first, Pétain seemed capable and willing to save France by acceding to Nazi demands, but without much strength. Over time, his collaboration became more and more objectionable and odious. German demands for the best champagnes and wines were among the events that drove increasing numbers of French men and women into resistance.

Grape growing and wine production in 1939 was little changed from the 19th century. Horses drew plows to weed the rocky soil that grows the best wines. Most tasks were done by hand. Owners were already suffering after bad weather and bad economic times had affected their harvests, thought most chateaux had stores of wine from good years back as far as the 1890s. Labor was essential for pruning, cultivating, and picking; chemicals like copper sulfate and fertilizer ensured that grapes would grow. Once the grapes were harvested, winemaking and bottling required labor and many supplies including sugar, bottles, and corks.

Under the occupation, supplies were scarce or unobtainable, and large numbers of able-bodied laborers were conscripted and sent to work in Germany, or they resisted and were arrested or worse. The book has many interesting details about how the few remaining family members coped, and how they negotiated with the Nazis who demanded that production continue in order to supply their requirements. Of course many of those left to run the vineyards were women, adolescents, or old people, often wounded veterans of World War I.

Each family or chateau had cellars that were often complex labyrinths of underground rooms or which were in natural caves. Back doors might open into fields or on hillsides. This made them ideal for hiding weapons, downed British or American airmen, and at times Jewish refugees, and for supporting the emerging resistance network. When the Nazis requisitioned large supplies of wine they often gave its destination -- this was valuable information that could be passed on to British intelligence.

The appointment of many Germans who had been wine merchants in France before the war was the source of much drama in the book, as the Nazi agents made demands on behalf of their overlords. Many in the German high command were wine lovers, though not Hitler. Wine was also used to improve the morale of the troops. Over time, the French figured out ways to hide the best wine. Nevertheless, vast quantities of high-quality wine were confiscated and sent to the East. In Paris, the best restaurants were assured supplies -- only Nazis were allowed to eat there while the French were practically starving. The details of many of these interactions are depicted in a fascinating way.

First-hand accounts from letters and diaries, occasional newspaper articles, and interviews with survivors provide vivid evidence for the way that French people experienced the conquest and looting of their country and how they struggled against the occupying forces. Deportations, confiscations of property like vineyards from Jews and others, and the appropriation of food and almost all other necessities to be sent back to Germany come to life in the authors' narrative. The memories of those who spent the war in POW or other camps were especially vivid.

As I read each chapter, I realized that the focus on wine was an effective starting point for the discussion of almost every issue of the war. I was especially interested in the slow and penetrating changes in the way that the French viewed Marshal Pétain and the Vichy government. At first, Pétain seemed capable and willing to save France by acceding to Nazi demands, but without much strength. Over time, his collaboration became more and more objectionable and odious. German demands for the best champagnes and wines were among the events that drove increasing numbers of French men and women into resistance.

Grape growing and wine production in 1939 was little changed from the 19th century. Horses drew plows to weed the rocky soil that grows the best wines. Most tasks were done by hand. Owners were already suffering after bad weather and bad economic times had affected their harvests, thought most chateaux had stores of wine from good years back as far as the 1890s. Labor was essential for pruning, cultivating, and picking; chemicals like copper sulfate and fertilizer ensured that grapes would grow. Once the grapes were harvested, winemaking and bottling required labor and many supplies including sugar, bottles, and corks.

Under the occupation, supplies were scarce or unobtainable, and large numbers of able-bodied laborers were conscripted and sent to work in Germany, or they resisted and were arrested or worse. The book has many interesting details about how the few remaining family members coped, and how they negotiated with the Nazis who demanded that production continue in order to supply their requirements. Of course many of those left to run the vineyards were women, adolescents, or old people, often wounded veterans of World War I.

Each family or chateau had cellars that were often complex labyrinths of underground rooms or which were in natural caves. Back doors might open into fields or on hillsides. This made them ideal for hiding weapons, downed British or American airmen, and at times Jewish refugees, and for supporting the emerging resistance network. When the Nazis requisitioned large supplies of wine they often gave its destination -- this was valuable information that could be passed on to British intelligence.

The appointment of many Germans who had been wine merchants in France before the war was the source of much drama in the book, as the Nazi agents made demands on behalf of their overlords. Many in the German high command were wine lovers, though not Hitler. Wine was also used to improve the morale of the troops. Over time, the French figured out ways to hide the best wine. Nevertheless, vast quantities of high-quality wine were confiscated and sent to the East. In Paris, the best restaurants were assured supplies -- only Nazis were allowed to eat there while the French were practically starving. The details of many of these interactions are depicted in a fascinating way.

The cruelty and rapaciousness of the conquerors makes this book a challenging read: it's just too depressing! Having recently spent a lovely vacation in Paris, I find it painful to recall such different times. The book is full of fascinating material and worth the effort.

Saturday, July 20, 2013

Medieval Paris

Modern Paris offers just a few clues for visualizing the city as it was in the Middle Ages. Always rich and vibrant, Paris was constantly being redesigned and rebuilt; the 100 little villages that have been absorbed into Paris have rarely retained even their 18th or 19th century street plan and major buildings. We weren't making any special effort to think about Medieval Paris on our recent trip; however, we saw a few medieval images.

In the Latin Quarter, little twisty streets just beyond the comparatively huge Boulevard Saint-Michel follow somewhat the same routes that they had in the Middle Ages, and retain some of the names. The very straight Rue Saint Jacques started on the other side of the Seine at the Tour Saint Jacques. Pilgrims began their walk to Saintiago de Campostello by taking this route.

First the route from the Tour Saint Jacques crossed the Ile de la Cite, not far from Notre Dame cathedral, though in those days, the crowded buildings in front of the cathedral might have prevented them from getting the spectacular view that's now available. Not far from their route also was the Sainte Chapelle, or royal chapel, which was built in the 13th century for Louis IX. In its current state -- restored in the 19th century -- the Sainte Chapelle is extraordinary for the vivid colors of its nearly uninterrupted stained-glass windows.

After crossing from the Ile de la Cite, the pilgrims had to walk past the Jewish quarter of Paris, which was just across the Seine from Notre Dame. In the 19th century, one of many reconstructions of these old medieval areas uncovered the old Jewish cemetery, whose tombstones are now in the Jewish Museum.

The pilgrims' route from the river also passed quite near the old Roman baths, where eventually the powerful abbots of the Benedictine Cluny monastery (located a little north of Lyons) had their Paris headquarters. The abbots began the additions to the old Roman structures in the 14th century so that they would have a place to stay during visits to Paris for both political and social purposes. The building now contains the Musee de Cluny, always one of my favorite museums in Paris. Our visit earlier this month was disappointing because the most famous possession of the museum -- the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries -- are not currently on display, as their exhibit space and other parts of the museum are in reconstruction.

The Cluny Museum, even minus the unicorn tapestries, is fantastically rich in sculpture, ivories, stained glass, metalwork, wood carvings, manuscripts, and other tapestries. It contains original stonework from Paris monuments that provide interesting insights into how the originals may have looked before the Revolutionary mobs of 1789 and just afterwards attacked the buildings, and before the 19th century restorers imposed their visions on churches such as Saint-Germain des Pres, which wasn't on the pilgrims' route, but wasn't far from it.

Seeing medieval art in Paris today also requires a visit to the Louvre, which also has a very large collection of medieval art. We enjoyed huge rooms full of beautiful tapestries, some of which used to be displayed at the Cluny Museum before one of the enormous expansions of the Louvre's space. There are many other opportunities to see traces of the Middle Ages in Paris, and several other museums with various collections of medieval works. It's impossible to grasp the riches of Paris!

In the Latin Quarter, little twisty streets just beyond the comparatively huge Boulevard Saint-Michel follow somewhat the same routes that they had in the Middle Ages, and retain some of the names. The very straight Rue Saint Jacques started on the other side of the Seine at the Tour Saint Jacques. Pilgrims began their walk to Saintiago de Campostello by taking this route.

|

| The Tour Saint Jacques |

|

| The Sainte Chapelle |

|

| Sainte Chapelle, detail of window |

After crossing from the Ile de la Cite, the pilgrims had to walk past the Jewish quarter of Paris, which was just across the Seine from Notre Dame. In the 19th century, one of many reconstructions of these old medieval areas uncovered the old Jewish cemetery, whose tombstones are now in the Jewish Museum.

|

| Jewish Tombstone, 1281, excavated from the old Jewish Quarter 19th century, image from the Jewish Museum Website |

|

| Filled-in Roman arches at the Cluny Museum |

|

| Capital from the church of Saint Germain des Pres, Cluny Museum |

|

| Capital in Saint Germain des Pres, repainted (maybe reconstructed) in the 19th century |

|

| Notre Dame Cathedral -- gallery of kings, reconstructed in the 19th century after destruction during the French Revolution |

|

| Cluny Museum: original head of a king from Notre Dame, discovered during excavations in the 1970s. |

Friday, July 19, 2013

Different Perspective on Paris

The Atlantic yesterday published a beautiful series of photos of Paris from the air, all taken on Sunday, Bastille Day. My two favorites of the 28 photos:

Thursday, July 18, 2013

Mona Lisa Here and There

|

| Yesterday at the Ann Arbor Art Fair 2013: Mona Lisa promotional t-shirts and give-away fans at See's Eyewear |

|

| Official Louvre shop: I resisted buying a Mona Lisa Rubik's Cube. |

|

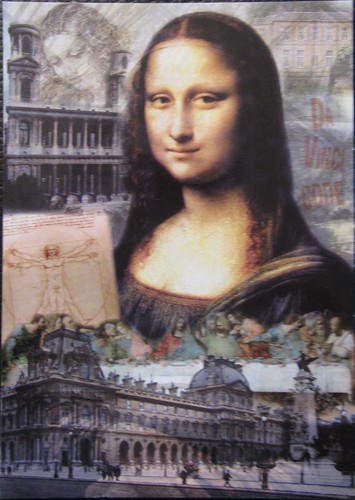

| Postcard for the Da Vinci Code (note Saint Sulpice upper left). |

|

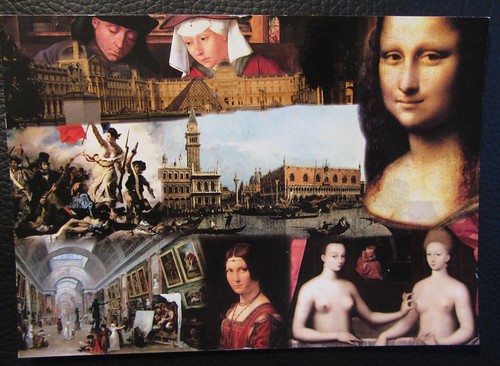

| Very Cultural Postcard |

|

| A different series of postcards |

For more images from my Mona Lisa collections, check my past blog posts here, here, and here.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Writers' Paris

A collection of posts about Paris, posted for Bastille Day last Sunday:

"25 Famous Authors' Poetic Descriptions of Paris"

My favorites, that make me think of my recent trip:

Gertrude Stein “America is my country, and Paris is my hometown.”

Edmund White: “Paris… is a world meant for the walker alone, for only the pace of strolling can take in all the rich (if muted) detail.”

Oscar Wilde: “When good Americans die, they go to Paris.”

Thursday, July 11, 2013

Paris: The Eiffel Tower

Pictures of the Eiffel Tower -- so ordinary! Everyone sees it from everywhere in Paris. Our friend Michelle sees it from her window. We had a view of it from one apartment that we rented on a long stay in Paris (unfortunately, we also had a very close view of an elevated Metro track). You catch glimpses of it while walking around, crossing a street, sitting in a cafe...

But it's actually very impressive! Look:

But it's actually very impressive! Look:

|

| From the Pantheon |

|

| Looking up... |

|

| The manege (merry-go-round) beside the Seine. |

|

| From the Palais de Chaillot gardens. |

|

| From the Trocadero |

|

| Evening at Belleville: both the Eiffel Tower and the Tour de Montparnasse on the horizon. |

|

| From Belleville, also with the Roue des Tuilleries (that is, the Ferris Wheel in the Tuilleries) |

Friday, July 05, 2013

Montparnasse

We've been staying in a hotel near Montparnasse, a neighborhood with lots of activity until late at night, a variety of appealing restaurants, and several large department stores in a big shopping center. Two famous things here are the Tour de Montparnasse, a huge skyscraper that dominates the Paris skyline, and the Cemetery of Montparnasse where many famous people are buried. Both of these landmarks appear in the photo above.

On a rather long walk around the cemetery we saw or looked for tombs of various famous people, including the mathematician Henri Poincaré, the writers Sartre and De Beauvoir, the singer Serge Gainsbourg, and the famous victim of French injustice Alfred Dreyfus. We were a bit surprised that although there are evidently some areas of the cemetery with all or mostly Jewish graves, other Jewish graves are interspersed with those of Christians. The French style of large marble slab-type graves and small mausoleums predominates. Some graves are very well maintained with fresh flowers and clean shiny marble; others appear abandoned, with moss and lichens on the stone and the epitaphs nearly effaced.

I have many more photos of diverse things I've done in Paris, which I'll surely continue posting when I get home next week to my quiet and much less strenuous life!

Thursday, July 04, 2013

Two Museums

This morning we started at the Marmottan Museum, which has a remarkable collection of Monet's own paintings that were willed by Michel Monet, his son, and by a few other collectors. There are several paintings by his friends and many by Monet himself. The museum is in a palatial private home that belonged to a family of industrialists in the 19th century. Their collections reflect a very different taste from the impressionists that line the walls of their elegant dining room, living room, and so on.

After a quick lunch in a cafe, we went to the Guimet Museum, a museum of Asian art. It's grand and large, also in the home of a wealthy collector. First we saw a special exhibit of works by Rosanjin, a Japanese ceramicist (examples above). In the exhibit was also a really entertaining ultra-modern art work that was a projection of videos of Japanese foods (Sushi, a Kaiseki dinner) onto a table where you sat and saw the food as if you were about to eat it. Pictures of someone's hands came from where your arms might be, and picked up the food and took it towards you, all in the projection. It's hard to describe, fun to watch.

The rest of the museum has monumental sculptures from Cambodia, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese art, and many other wonderful things.

|

| Southeast Asian sculptures. |

|

| Southern Song Dynasty ceramics |

Wednesday, July 03, 2013

A Long Day at the Louvre

We had an extremely pleasing visit to the Louvre today. To start: we were concerned that we would have a very long wait in line, but the actual wait was only around half an hour including the security line, buying the ticket, and getting into the museum. We think that we were lucky -- and also, we made an early start. So we were in the museum just before 10:00 this morning, we ate lunch in the very pleasant (though expensive) sit-down dining room, and we stayed until around 3:30.

The Louvre is like a conglomerate of individual museums, which ideally would be worth several hours for each one. We visited quite a few departments: Italian Renaissance art, including Mona Lisa (whose adoring crowds have grown unimaginably). Medieval art, including a vast collection of tapestries, ivories, enamels, and pottery. Islamic art in an enormous new area that just opened last September. German and Dutch painters including Metsu, several members of the Breugel family, Rembrandt, Vermeer, and many others. French painting of all centuries up to the late 19th, for which one must go to the Orsay Museum. Some donated collections that are shown intact out of respect for the collectors' wishes, which include an occasional Monet, Degas, or Pissaro. Near Eastern art from many centuries and cultures ... It's overwhelming.

Taking photos of actual paintings is impractical, but here are a couple of views from the windows:

In one of the rooms full of drawings and sketches, I learned of a painter that is new to me: Elisabetta Sirani, who lived from 1638-1665 in Italy. I've looked her up -- she was very accomplished, and painted many full-scale oil paintings as well as this sketch:

The Louvre is like a conglomerate of individual museums, which ideally would be worth several hours for each one. We visited quite a few departments: Italian Renaissance art, including Mona Lisa (whose adoring crowds have grown unimaginably). Medieval art, including a vast collection of tapestries, ivories, enamels, and pottery. Islamic art in an enormous new area that just opened last September. German and Dutch painters including Metsu, several members of the Breugel family, Rembrandt, Vermeer, and many others. French painting of all centuries up to the late 19th, for which one must go to the Orsay Museum. Some donated collections that are shown intact out of respect for the collectors' wishes, which include an occasional Monet, Degas, or Pissaro. Near Eastern art from many centuries and cultures ... It's overwhelming.

Taking photos of actual paintings is impractical, but here are a couple of views from the windows:

In one of the rooms full of drawings and sketches, I learned of a painter that is new to me: Elisabetta Sirani, who lived from 1638-1665 in Italy. I've looked her up -- she was very accomplished, and painted many full-scale oil paintings as well as this sketch:

Monday, July 01, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)